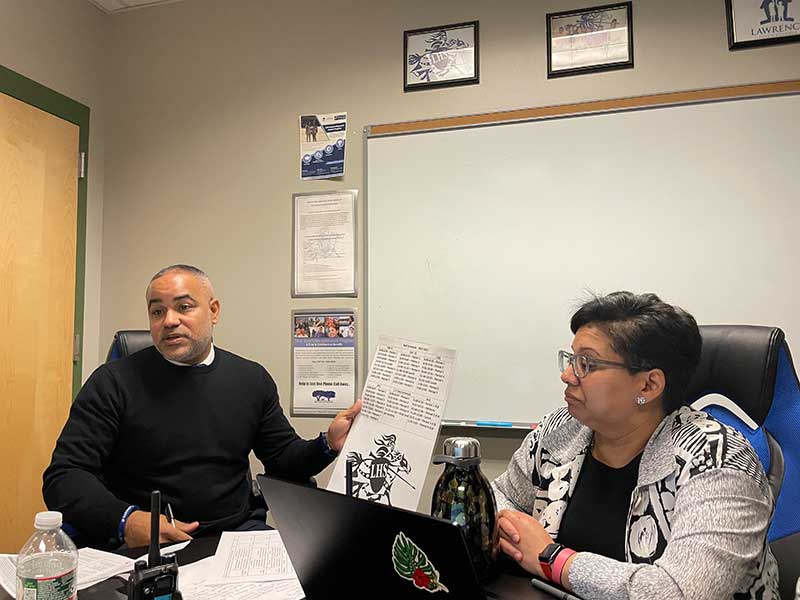

I had the privilege of visiting Lawrence High School (LHS) along with colleagues from Lynn Public Schools and Harvard Graduate School of Education. Even though the campus is huge, with over 3,000 students, there is a sense of calmness, connection and purpose inside. Our hosts for the day were Victor Carballo-Anderson, head of school, and Jeanette Jimenez, principal of UNIDOS, one of the five schools on the campus. UNIDOS is specifically geared to recent arrivals to Lawrence MA and the United States. There are about 460 students, grades 9-12, in this school. The other schools are: Lower School (grades 9 and 10), Upper School (grades 11 and 12) and Lawrence High School’s exam school, Abbott Lawrence Academy.

We visited a few classrooms in all of the schools, except the exam school.

Here are some of our takeaways:

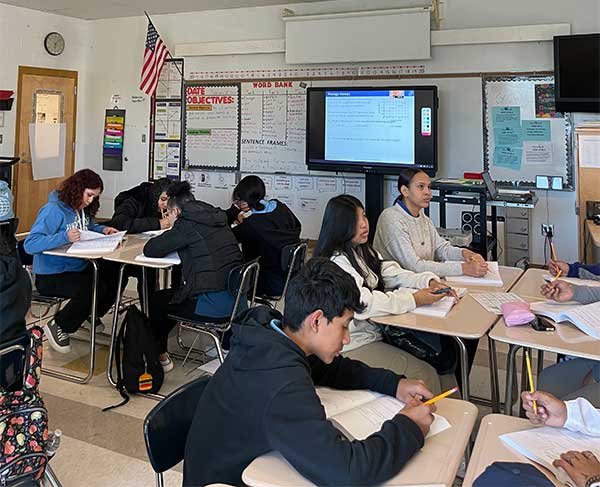

In each classroom, students were working diligently. We saw no one with heads down; no one off track; no one deliberately pulling focus away from the activity. Most striking, in every class students worked in groups–and with ease. “Turn and talk with your neighbor,” “Who is leading the discussion and who is reporting out,” “Check with your tablemates to see if they got the same solution” were all requests that students knew how to respond to. Collaboration was a skill that they had mastered.

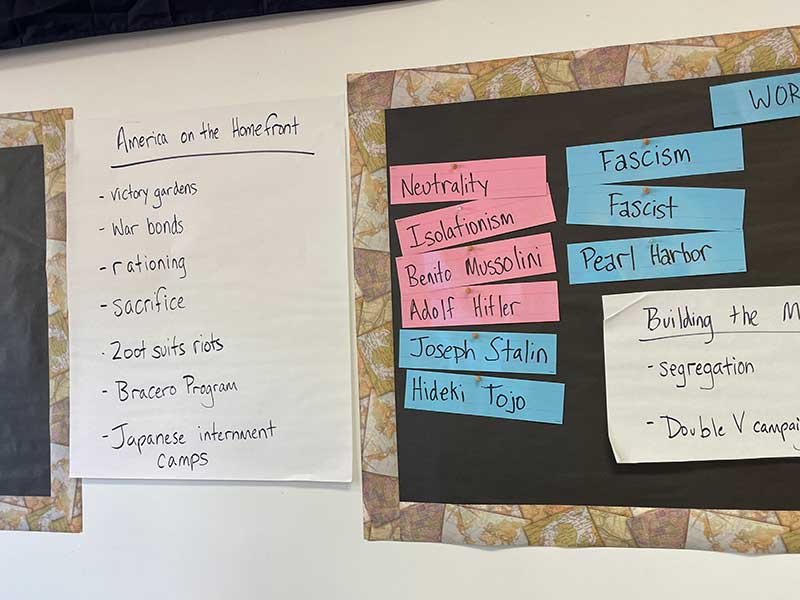

Students in an upper level UNIDOS history class responded to this question: The Atomic Bomb: Did President Truman make the correct decision? They had just read a challenging primary source document, in English, and, in table groups, were discussing the facts to ensure that they understood. They were working with dictionaries, not with computers. The teacher explained that he didn’t want them using google translate but rather one another and a dictionary. The next task was to individually fill in a graphic organizer to help write their essays. The teacher had created this organizer to support their emerging English skills. For example, for the thesis: [Yes I agree] or [No, I disagree] that Truman made the correct decision with the atomic bomb because of reasons [give 1 and 2 reasons].

“I want to give them scaffolding,” the teacher explained to us, “but I know they can do this high level work.” And they did. The classroom was abuzz as students debated with one another before they began to write quietly. Some students expressed their ideas in Spanish with one another and even checked their understanding with the teacher in Spanish. He responded in English, but the translanguaging was impressive.

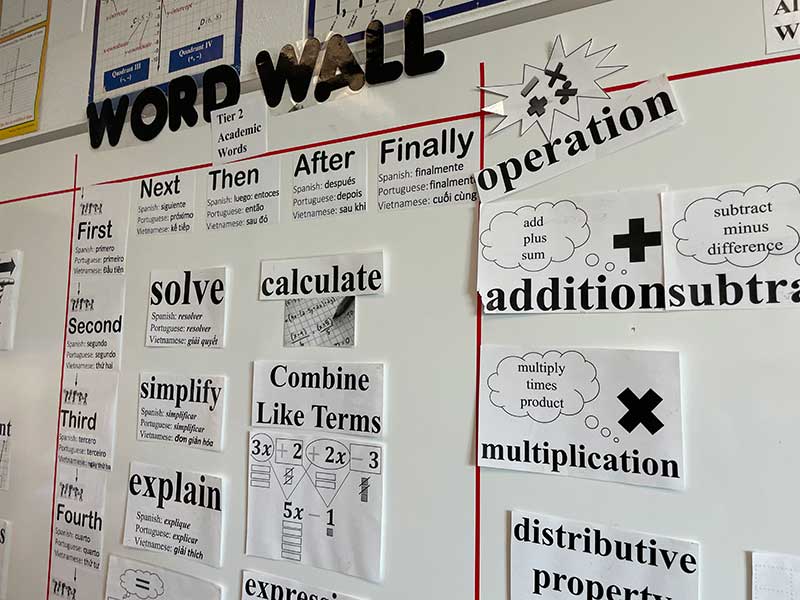

We saw the same kind of translanguaging in Math class. Students were digging into word problems and equations as part of their Illustrative Math curriculum. The set up was the same: students worked in small groups; checked their understanding with one another, easily asked questions of tablemates and offered solutions to the whole class while the teacher recorded answers on the Smart Board. Again, the feeling was one of: we are all learning together here. Are there other possible solutions? How did you reach that solution? Math was presented as another language to master and explain. I had to hold myself back from participating.

Jeannette, UNIDOS principal, explained that as students enter her school, she and her staff strive to get to know each one of them. “We need to know about their learning experiences prior to coming here. Have they come from the DR [Dominican Republic] or walked across the border from Guatemala? We need to know what kind of trauma they’ve been exposed to. That will impact how they learn. Of course we need to know something about English and math skills, but really we need to know about them: as people.” A deeper understanding of the student journey translates into the humanization of each individual student who enters LHS. While students are codified by their “ID,” knowing the student’s journey allows teachers and leaders to make comprehensive and individualized plans for each student. The model is this: extending the idea of an “IEP” [individualized education plan] and applying this same concept with multilingual learners/SLIFE students. LHS recognizes that teaching and learning cannot occur unless the whole child is taken into account, in particular for new arrivals to the country.

We visited 9th and 10th grade classes in the other schools, too. Victor explained that they’ve put a lot of resources into co-teaching in these lower grades. We saw evidence of this in a biology class where one teacher was leading while another teacher who had ESL and Special Education expertise was supporting students. Again, everyone was an active participant and seemed invested in the lesson.

There is not one way to improve a school, but clearly Victor and his team have figured out some important strategies.

Size. A student belongs to a school within this big campus. This is critically important since most students are arriving from small elementary and middle schools. Even a school of 600 feels big so the Lower school is broken into cohorts to give more of a sense of community and individual attention.

Each principal has autonomy in running their school, but all five principals meet with Victor (the campus head) to work through instructional and budget priorities. Each principal has the ability to determine budget, staffing, curriculum adoption, and scheduling. Yet, at the LHS campus, they all work collectively under one shared vision and mission in which all leaders compromise to create a coherent educational experience. The shared belief is that one’s autonomy should not override an LHS student’s collective experience and success, regardless of their assigned academy or grade level. Principals, in collaboration with the head of the school, maximize shared leadership and allow full autonomy while not compromising the collective welfare of students. This decentralized model includes some centralized leadership–and always grounded on student outcomes.

For example, students are offered opportunities for early college classes beginning in 10th grade. Students can choose to continue to a cost-free Associate’s degree at Northern Essex in the “Early College Scholars” program. UNIDOS students are included in the program and have specialized support to succeed in Early College courses.

In the reopening of school after the pandemic, student behavior at LHS was very dysregulated and the culture of the school was in disarray. Some will remember the negative newscasts about students there in 2021-22. Victor has worked hard with his administrative team and the faculty to underscore that disruptive students are a small percentage of the student body. The mantra is: “Instruction must continue.” But he’s also done something else: there is now a Culture Team under the direction of a Culture Specialist and even a Restorative Justice room. The physical room gives teachers an opportunity to re-set. If a teacher has had a bad day or a week or just needs to work through issues in a different venue, they sign up for this space, which has cozy furniture, soft lighting and a very different vibe than a traditional classroom. “Here, teachers and students have a chance to start again.” Resetting isn’t seen as a negative, but part of the learning process.

Victor shares more about his views on school culture. “We insist that teachers do their piece in the classroom to set a positive culture. Everyone owns a piece of this. Instruction can’t stop because of school culture issues that impact a few. The culture team is there for that extra support.”

Alignment is also key. It was clear that the adults at Lawrence HS are aligned. “The job is too hard if we are moving in so many contradictory directions, “ Victor tells us. “We are all working on getting better. It’s about progress, not perfection. Teachers tell us what professional development they need; our job is to provide that. And then, we have to be consistent.”

We saw consistency. All classes working in groups; all students working on high quality instructional materials; many classrooms with co-teachers; and all with teachers who were prepared with their lessons, asked complex questions of their students and expected their students to rise to those high standards.

There is no silver bullet for school improvement; however, the theory of change was clear: If we have a shared understanding of our instructional vision, student achievement will increase. “We had to work together to create a shared understanding of our instructional vision. At first everyone had a different definition. We can’t have conflicting definitions. Our students won’t take us seriously. They are too smart for that.” After many conversations, the leadership team’s strategy for improvement evolved: new high quality curriculum, consistent and coherent professional development, and regular coaching, particularly for teachers new to the profession. Many schools do that but then don’t stay the course. LHS keeps the vision of achievement for all students front and center and has worked with the same curriculum for over three years. Consistency matters to teachers. Support with high expectations also matters. And continuing to articulate the vision matters.

And consistency matters to students. That’s how they learn to trust adults. Each classroom we visited reflected the above mission. And, all teachers had word walls, and language and content objectives. An organized presentation does not mean instruction will be good, but we saw teachers point to words on the word wall and reference objectives. Especially for ELLs, these are helpful tools. Clearly, teachers had thought about language objectives as part of their content: that gives all students opportunities to build language skills while learning content, too.

Some other wins for this school that we can all learn from:

How do you grow your own teachers? How do you motivate, for example, cafeteria workers or parents or current students, to become paraprofessionals and then certified teachers?

How do you recognize mistakes? This school didn’t recognize, at first, the enormous trauma of the pandemic for teachers and students. After being out of school for almost two years and being one of the hardest hit communities in the state, a lot of healing had to happen and slowly. The introduction of the culture team and clarity about standards and procedures was important to resetting. Specifically, the culture team is responsible for targeted student interventions that are data-driven. The team is managed by a campus restorative justice manager who collaborates with the head of the school to ensure the coherent application of processes and procedures campus-wide. In addition, on a quarterly basis, students and staff are surveyed to gather information regarding the areas of growth (celebration) and areas of need campus-wide. These surveys set the foundation for strategic culture interventions, budget decisions regarding culture-related staffing, and professional development needs. These culture “moves” also inform classroom moves connected to teaching and learning. LHS recognizes that school culture needs do not manifest in isolation but are often a result of a disconnect between the curriculum taught and enacted, as well as students’ sense of belonging to LHS.

How do you offer and provide support for high level curriculum for all students? All students, including newcomers, have access to Pre-AP, AP and high level standards based curriculum. It matters less, at this point, that students are taking the AP test. Now it’s about exposure and excitement about ideas.

How do you move resources so that the most vulnerable and “needy” students get the most? By introducing co-teaching in the lower house schools and by providing as many resources as possible to newcomers, LHS has been clear that when these students succeed, everyone will.

Surely when Victor arrived at LHS, many priorities demanded his attention, but five years later it is clear that by staying the course, continuing to articulate the vision and build his team, which includes teachers, students are reaping rewards.

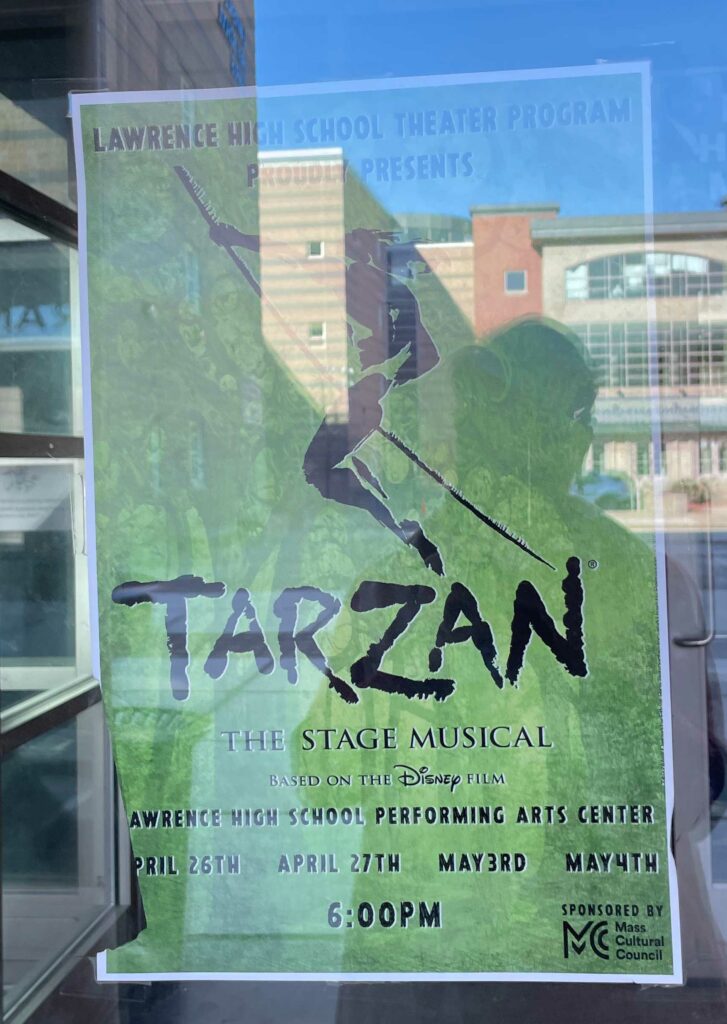

I left filled with hope and energy for the promise of these students and their teachers. And, in our short visit to the Performing Arts division, I was energized with the promises of what can happen with a robust arts curriculum at LHS.

LHS classes, at their best, are led primarily by students, with teachers actively facilitating, differentiating for access and support (including challenging/extending), providing criteria-referenced and actionable feedback, and deepening understanding through open-ended questioning and “shining the light” on excellence. LHS classes aspire to be joyful places where diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging thrive.

LHS Mission/Vision, 2024