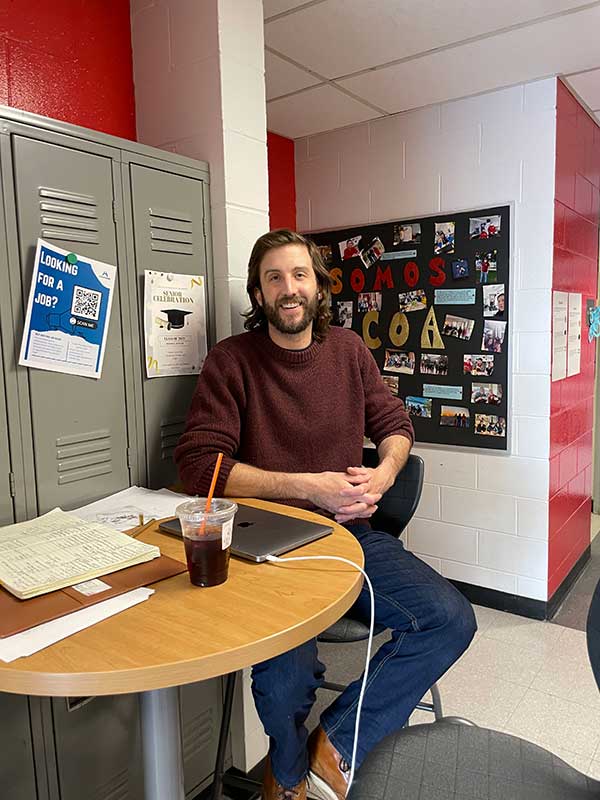

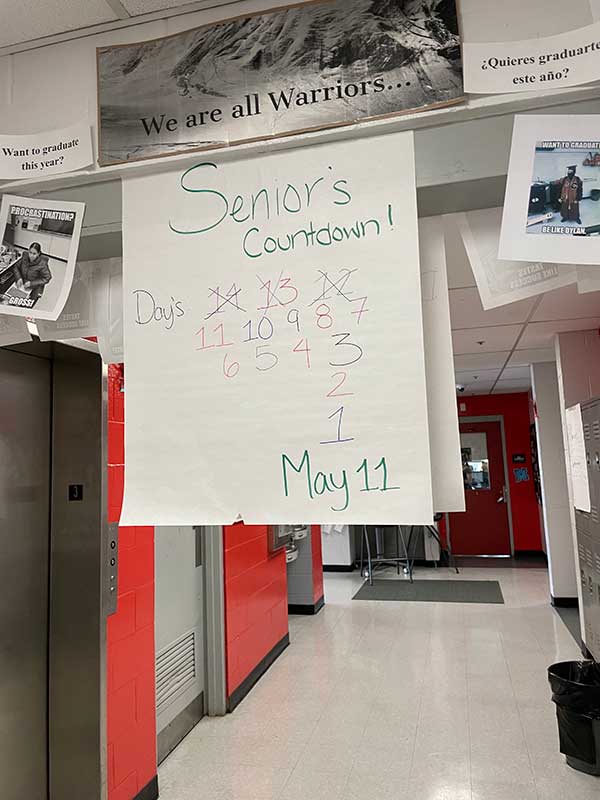

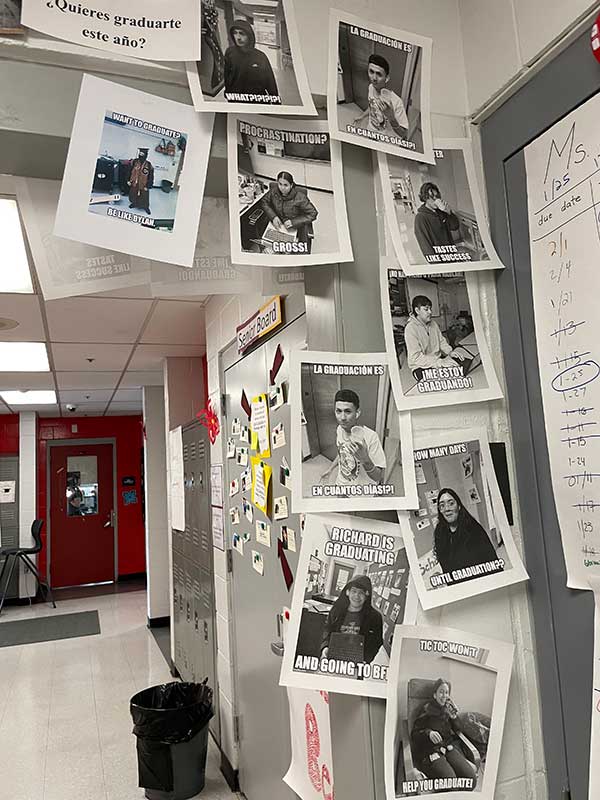

Chelsea Opportunity Academy (COA) sits in a far wing of Chelsea High School in Chelsea MA. I have been visiting this high school since the mid-80s in its various iterations and changes. I always leave energized by the students and faculty I meet. Adam, a former student teacher at Boston Arts Academy, where I first met him over a decade ago, is my host. He is now the assistant principal of this alternative school. He proudly shows me the school’s space and his own “office,” which is literally a hightop table in the middle of a hallway with a view of almost all classrooms. Student work is on every wall and special attention is paid to seniors and the fact that they are graduating. Lunch has been delivered from the cafeteria and sits on one of the tables in the hallway. Another hallway has clothes hanging from lockers and shirts and pants folded neatly on a table. This is the free clothing store. Students can take something that they might need. No questions asked. On another board there are sticky notes with shout outs which spell out COA. When the initials are complete, the board is “erased” and notes start again. Notes range from “Shout out to Ray Ray for completing Gentrification in the City of Chelsea (a history course)” to “Marvin for returning to school and proving that Every Day is a New Day.”

CHS has approximately 1700 students and COA, its alternative school, serves approximately 150 students. Like many alternative students, the small size is critical for the students’ sense of safety and belonging. Students dropout of high school for many reasons including: the need to work, caring for siblings and/or family members, conflicts with peers or teachers, difficulty learning in a large school, mental health or legal challenges. They find their way to COA and the two most notable differences are: a flexible academic schedule and a huge emphasis on caring relationships with adults (and peers).

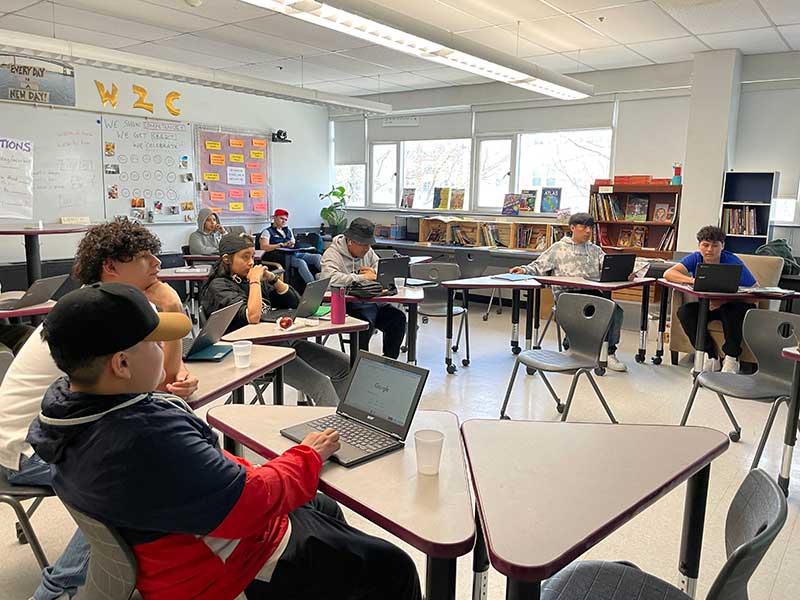

Students talked with me about how “teachers understand that I’m working forty hours a week and need to come in later in the morning.” Classes are set up with tasks and assignments that students need to complete but there is no penalty for needing to go slowly and thoroughly. The notion that you have to pass English 10, for example, doesn’t exist here. Estephanie shows me in her chrome book where she is in her current progression of assignments. Each student in this ESL class is working on a different set of assignments and activities. In order to ‘pass,’ they will need to satisfy a series of tasks as well as demonstrate competency in key areas such as create a question and establish and support a claim. Unlike many competency based schools I’ve visited, at COA the competency wheel (see below) is actually manageable. If I were a student I wouldn’t get lost in the layers or the nuances of the rubric (even though one of the criterion is ‘nuanced.’) Students are measured on whether they are learning, functional or nuanced in their achievement of the competencies.

Emerson explains that the school is “mas practico,” or more practical for him since he is working two jobs. Each student emphasizes that the teachers care about them. That’s evident in the way that Sela Kenen begins the class by reminding students that they have to tell her when they don’t understand. “That’s your job; tell me if you are lost. My job is to help you understand.” She says this bilingually, going back and forth effortless in Spanish and English. She welcomes me immediately as do all the students. All of the students are Spanish speaking and no one seems surprised that I speak Spanish, too.

I meet Mathew: a graduating senior. He shares his Capstone with me, a culminating presentation that both demonstrates a series of competencies and also indicates that a student is ready for graduation. His journey to gain self knowledge is impressive and it’s clear that COA has been where he learned how to do that. Through a series of slides he describes how he was kicked out of most of his schools, was living on the streets and involved in gang and other illegal activities involving drugs and guns. “Basically, I was defiant, involved in lots of bad relationships, and had a 14% in my classes at the regular high school. Then I heard about here. This is a second home.”

He is very articulate about the person he used to be. “I gambled, smoked, drugs, guns. Gang members were my family. Doing wrong things got easier and easier. I was good at all that. I got a lot of recognition.” He explains that the transition to leave the streets and embrace a more stable life was not easy. “I don’t have to be a prisoner of my past life. I can have a future.” He had a lot of help from teachers and a community based program called ROCA to navigate and then negotiate leaving gang life. “My teacher here taught me to tell my own story, to understand myself. I learned to write to express myself. That was powerful.” He also took a course in finances. “For the first time school gave me skills I really wanted and needed like about credit and debt and even about savings. I want to start my own sneaker and clothing business, but legally this time.”

He understands that he deserves to have future goals and he wants them. He plans to join an apprenticeship program in plumbing when he graduates. He has gotten his drivers’ license. “School even helped with that.” He acknowledges, somewhat sadly, that for a long time only his gang involved friends looked out for him, but it doesn’t have to be that way now. “My past is not a life sentence. It’s okay to be who you are and who you want to be. Everyone has a story; we just need to learn to tell it.”

Perhaps that should be the motto for COA.

I left filled with a sense of hope for the students in this school. Adam has a chapter about this small school in the book I’ve co-edited: Building Democratic Schools and Learning Environments: A Global Perspective which will be published soon.