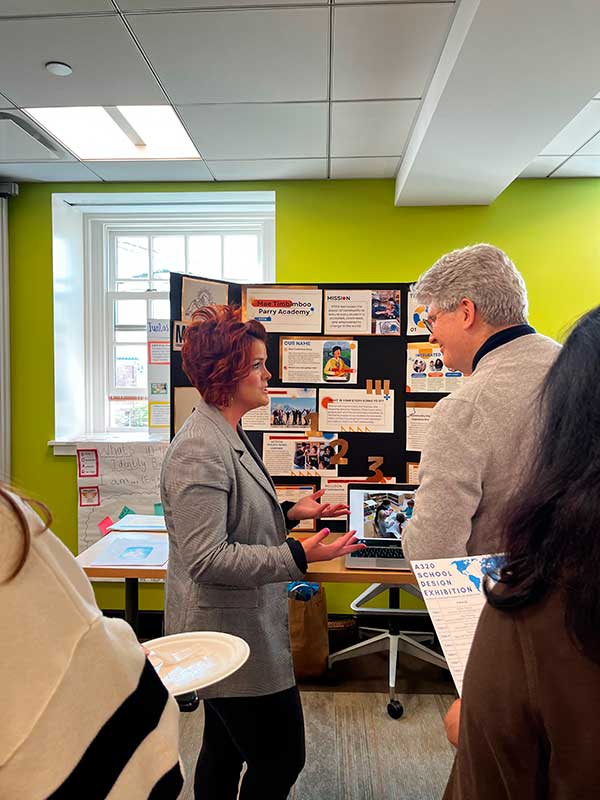

A few weeks ago, I proudly stood in the midst of my HGSE classroom, vastly expanded without the dividing expandable wall, and watched my graduate students from my Building Democratic Schools course preparing for their final exhibitions. Twelve weeks ago I had assured them that each of them would, indeed, design a school or a nonprofit.

Every inch of the room was now covered in colorful Science-Fair-like boards and tables supporting planting materials for one school, and stuffed animals for another. Artifacts of all shapes and sizes were part of the displays. All semester, students tirelessly worked writing and revising their mission statements. Some had even been coerced to sing them in front of the class. (I always say that mission statements have to be sung or no one will remember them.) Students had designed their ideal schedule, described their curriculum and assessment systems; they had developed governance ideas; created budgets and returned again and again to the communities they were designing with and for. They asked: is this what my community needs? What is my evidence?

I knew (but I’m not sure my students did) that during the next couple of hours they would truly begin to feel a sense of pride in their designs. Over one hundred educators ranging from as young as age three to over 75 came through to listen, learn, discuss, probe, encourage, question and react to these designs. As one of my student designers said, “the exhibition allowed me to exhibit my ideas in an official way to an audience…Something that I have held internally [became] an external, public project… and I could think about what kind of feedback I needed at this stage.” In the mid 1980s that is exactly the way Ted Sizer discussed the power of exhibitions that were public facing with a “real” audience. It is something akin to theater. The play is only complete when it is performed on stage.

Lydia Cao, a former student, and founder of BirdHouse, brought some of her students from Providence, Rhode Island. These young people, who have experienced a very different kind of education mostly homeschool based, were delighted by many of the design aspects of my students. They scurried around, grabbing snacks between stations, and probed the graduate students about why they decided on that schedule or this logo or that kind of curriculum.

Cole Moran, a talented young educator from BPS, brought his high school students who were truly the stars of the day. Many of them had joined our classroom previously to workshop the final designs so the highschoolers had a sense of pride about what my students had changed or explained better. “I like your logo so much better,” Danielle acknowledged. Two students gave Sona huge props for really integrating social emotional learning in high school. “That’s so important and most schools just brush over that.” Another student, a recent immigrant to the U.S, was excited by all the schools designed by graduate students from Vietnam, Thailand, India and Japan. “I’m glad to see these democratic schools will also exist outside of the United States,” she told me.

Rigzen, from Ladakh, India, shared the stage with an entire community of elders who had come from various parts of the world to support their “sister” in her quest for improving education for the young people in her small village. The fact that so many came was astonishing to many of us. “My community showed up,” Rigzen said as if it were the most natural thing. Their presence and commitment to this new endeavor tells me that Rigzen’s design, the Village Lab Foundation, will open. She has elegantly incorporated the wisdom of the elder generation alongside young college graduates as youth workers. The young people of Ladakh will surely reap huge benefits.

Throughout the class we explored pillars of democratic education, including: student voice and choice, a focus on equity, stakeholder involvement to collectively address society’s most urgent challenges. All semester we asked: how do or don’t these ideas resonate in your context?

Student Reflections on the Exhibitions

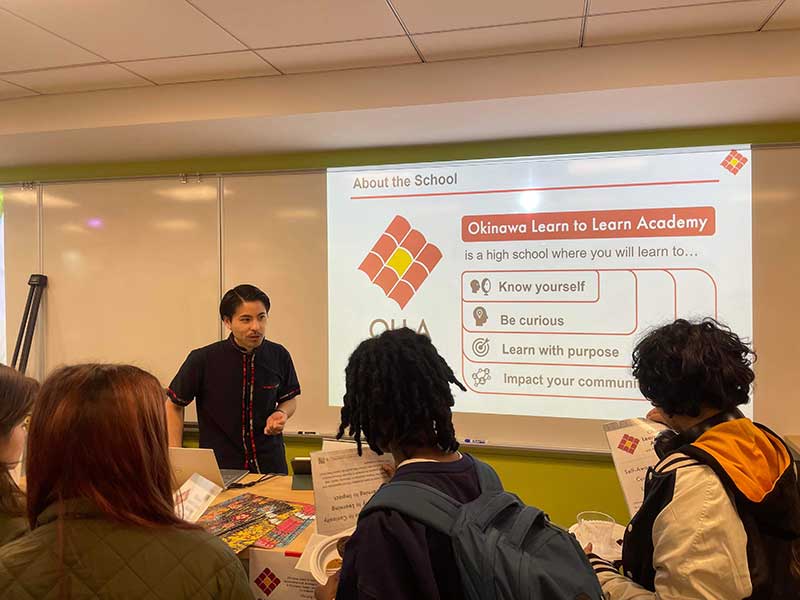

Masa, from Japan, designed OLLA, the Okinawa Learn to Learn Academy. Early on, I was drawn to this new school since the phrase “learn to learn” is what then founding teacher, Anne Clark, now BAA Head of school, used to call out in the corridors to get kids to class on time. I always loved the phrase and its layered meaning. In his final reflection, Masa shared,

“There is very little or no democracy, equity, and freedom in the current education system in Japan. The students, parents, and educators I interviewed did not feel that their voices were heard…the concept of equity is not well known in Okinawa and Japan. There [are]people who believe that university entrance exams are “fair” as anyone can pass if they study hard, implying that those who cannot pass just did not work hard enough. I believe that democracy, equity, and freedom each needs to be addressed to bring hope. I need all the various stakeholders of my school to be hopeful about their learning opportunities.”- Masa

Christina, the designer of Seedlings Academic in Houston wrote, “It’s important to allow for freedom and autonomy, but we also need to think about our collective community and how our choices and actions impact the people around us. Our voices should all be able to be heard, but we also have to think critically about how we’re ensuring that those who have been historically marginalized and oppressed are receiving the things they need to truly thrive.” She goes further and reminds us that there is no silver bullet or quick cure for what ails schools both nationally and internationally. “I’m leaving this semester even more firmly believing that change can (and should) happen at the local level. I’m wondering how (and if) we can ever find alignment as a community/society on what the purpose of education is.”

I’ve been grappling with the same question for over 40 years. Like Christina, I remain excited “to think about the opportunities to continuously design and redesign schools to meet the evolving needs of the people they aim to serve.” This idea of how schools evolve to meet the current moment is what carries me forward.

James Jack (my teaching assistant and teaching partner for the last three years), designed experiences in class for our students to actually practice democratic activities. At least 6 weeks before the actual exhibitions we gave students opportunities to make decisions about how the day would unfold and be organized. We briefly explored consensus, pluralism and simple majority for making decisions. As Manami wrote, “I am also thankful that our class got to run the exhibition together. Even though we were disorganized at first, I think everybody split themselves into committees that they thrive in the best. I also appreciated our democratic voting system where people got to provide feedback before making a group decision.”

In debriefing with James, I realized that schools and classrooms may be one of the few places where young people are actually exposed to the workings of democracy at the local level.

Eve echoed these sentiments. “Democratic schools do not happen by chance. They are intentionally designed, but democracy, as we know, is a messy and complicated process.”

Throughout the semester, we asked students to talk to their communities, and to always include the young people they were designing for. As Megan affirmed, “Our design process required me to consider the voices of young people in a way that I hadn’t before. I often have had conversations about honoring and respecting the voices of students in the classroom, but had seldom thought about how this should happen in the broader educational landscape.”

Kelsi wrote, “I used to think students need a seat at the table; now I think students are the table.”

For two hours on the last Thursday in April, I watched as my graduate students displayed a world in which democratic learning environments have a chance to thrive. I am enormously proud of them. This short video shows some of the energy and hard work exhibited by my students.